Upwards of a decade ago, a mother called me and asked what I might advise concerning her son, who was at risk of going “Off the Derech.” There were two problems. First of all, I never experienced the challenges of a frum teenager, and at that time had not yet been the parent of one. And second, my Kiruv work has always surrounded giving people a taste of Torah, a bit of inspiration. But even Kiruv must involve not merely teaching, but showing people a Torah life — developing an emotional attachment to Torah rather than simply whetting the intellect. I suspected even then that someone who grew up in a frum environment wasn’t going to be drawn back by intellectual discussions. I knew that I wasn’t the right person to advise her.

In a piece published on Torah Musings, Rabbi Dr. Joshua Berman, professor of Tanakh at Bar-Ilan University, addresses the topic of young people leaving religion. He reviews a book describing the reduced attachment to religion of “millenials,” today’s young adults, and Rabbi Berman infers that “the struggles in our communities are part of a larger trend challenging traditional religious life in western culture” and are “not because of bad parents, or bad schools.”

Rabbi Berman is both a good friend from years past and a respected thinker, and his article is an excellent starting point for discussing this topic. Perhaps, too, there are differences between charedim and Modern Orthodox at play here. But I believe that by focusing upon intriguing similarities, he missed crucial differences between other communities and our own. Those differences show that both families and schools are making a very positive difference in our community — and also that there is more that both could be doing.

The most critical and revealing difference is that we are not facing similar losses. I say this from a Charedi perspective — I have heard from campus Kiruv professionals that there is a very high attrition rate for Orthodox students at four-year secular colleges, perhaps higher than 25%. I don’t know if this is correct, or what the numbers might be for the larger Modern Orthodox community, but contrary to what a Washington Post writer claims to have heard at a Tikvah seminar, the number of Charedim leaving a Torah lifestyle is nowhere near that high. Even the Pew Survey’s figure — that 17 percent of young adults raised Orthodox no longer are — seems outlandishly high where the Charedi community is concerned.

We may be so (justifiably) concerned about each individual who goes “OTD” that we imagine the numbers to be larger than they are. A recent article in Time magazine compared dating problems for women among the college-educated, the Mormons, and the “Yeshivish” charedim. What all three share in common is an oversupply of women. Women are now more likely to seek a college education than are men, apparently by a margin of 4:3. The Mormon Church is affected by the national drop-off in religious enthusiasm, which disproportionately affects men, to the point that one survey estimated there are now 60 Mormon women for every 40 men.

According to demographers, however, the cause of the Yeshivish “Shidduch crisis” is a combination of a rapidly growing population and boys marrying girls a few years their junior. There are reported to be 112 19-year-olds per 100 22-year-olds in our community — and since 22 and 19 seem to be the preferred ages to “enter the market” for boys and girls respectively, this creates a problem.

Why is this relevant? Because it is apparently true in our community, as outside it, that men are more likely to leave religion. According to Footsteps, an organization catering to Charedim (primarily Chasidim) turning secular, only one-third of their clients are women; by their accounting it seems men are twice as likely to leave. This being the case, I previously thought — and believe I wrote — that this, plus anecdotal evidence that women are marginally more likely to become Baalos Teshuvah, could be a factor in the “Shidduch crisis.” Yet there is no parallel issue among Chasidim, simply because they tend to marry people their own age — the fact that more boys than girls leave seems to have no demographic impact. And no one quoted by the author believed that the greater numbers of boys going OTD was a significant factor in the Yeshivish community either.

The second difference, which begins to explain our greater retention rate, is in the area of education. In this country, the two largest groups offering parochial schooling are the Catholic Church and Orthodox Jews; previous history suggests that the reason why we are now retaining such a high percentage of young adults is because our schools are by and large doing their job. The Mormons deliberately do not provide parochial alternatives “where there are adequate public schools available,” and the Southern Baptist Convention seems to provide far fewer parochial schools for their sixteen million SBC members than there are chadorim and day schools. The exposure to foreign ideas and lifestyles to which Rabbi Berman points comes at a later age for our children, and after a much more solid grounding in religious thought.

And finally, there is a significant difference in philosophy. Christianity is about faith, it is something they agree (and state proudly) cannot be proven. Judaism is, on the other hand, about things we know — beginning with the testimony of our collective ancestors. Rav Shlomo Wolbe zt”l told a chabura of Yeshiva students that each person should have five proofs why he knows that H’ created the world, and five proofs that H’ gave Moshe the Torah. He didn’t talk about belief, but about proof.

All of this being the case, I will both agree and disagree with Rabbi Berman concerning parents and schools. I agree with him that we don’t have a problem of bad parents or bad schools. But I do feel there is more that we could be doing, and would offer two of my own suggestions, one for parents and community that concurs with two of his, the other an addition for the schools:

1. Keep the Door Open — A student at Stern College, herself a Ba’alas Teshuvah, made the following insightful comment in an online forum:

I have never seen a memoir or heard of a case of someone going OTD from the Charedi world that didn’t involve some familial or personal abnormality, including being raised by grandparents because parents were unfit, having a parent die young, having parents who were BTs and therefore less family support, mental illness, etc. If the families were secular these would be seen as things that could make life difficult, but since they’re not, frumkeit is presented as the “causative” difficulty.

When challenged about other cases, she clarified that she meant the ones who had written or thought about writing memoirs, not those who simply “fall off” from observance. But one can say more generally that the great majority of those who leave the Torah community — including those who grew up in warm, loving, completely “normal” families, and had excellent relationships with their schools and teachers — do so primarily for emotional rather than intellectual reasons. It no longer makes sense (if it ever did) to cut off contact with errant family members in order to both reprimand them for bad decisions and deter further losses. On the contrary, maintaining an emotional bond is the best way to bring someone back.

The very title of Shulem Deen’s memoir, “All Who Go Do Not Return,” is indicative. He is not stating a rule that when one leaves, one never returns. On the contrary, he writes that not everyone who goes, returns — correctly implying that many of them do. Many consider Teshuvah after leaving our community for a time, and return is most likely to happen when our community keeps the door open and the lights on. Those “exploring” outside the realm of observance should feel confident that they will be respected for rejoining us, rather than mocked for their departure, whenever they reappear in our shuls and communities.

2. Teach Emunah and Face Questions — The Internet is a problem because it can easily be a vehicle for the Yetzer HaRa. It should not, however, be an intellectual obstacle. Certainly we should not have a situation where a formerly Chassidic man claims that the sight of dinosaur bones started his outward journey. Even if we agree that this is ultimately an excuse rather than a real issue, why should he even be able to say such a thing?

Rabbi Berman writes that we must “legitimate the expression of doubt.” But “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” — knowing that our youth will face intellectual challenges and questions, we should be teaching the answers. The Haggadah gives the same posuk from the Chumash (verse from the Torah) to the child who does not know how to ask, as to the rasha. In other words, don’t wait for problems, teach the child the answers before he even knows how to ask hard questions. This is especially true in those communities and schools where children routinely go on to four-year secular colleges, but today almost everyone can expect exposure to foreign ideas and influences.

Parents and schools need to be part of addressing today’s challenges, rather than hiding from them. A local parent told me of a recent summer camp interaction between girls from Baltimore and New York. The New York girls were amazed to learn that in Baltimore schools they have open conversations about fundamentals of Emunah. As it turns out, an educator at the school attended by one of the New York girls is himself a well-known lecturer about these topics. But he can’t teach about them in his own school, because the parents won’t stand for it.

Similarly, the Rosh Yeshiva of a high school (outside New York) nixed a talk about Torah and science because it might “raise more questions than it answers.” Rav Wolbe zt”l said the opposite: “In a world where ‘הַשָּׁמַיִם מְסַפְּרִים כְּבוֹד-אֵ-ל; וּמַעֲשֵׂה יָדָיו מַגִּיד הָרָקִיעַ’ (‘The heavens declare the honor of Hashem, and the sky tells the works of His Hands,’ Teh. 19:1), it is impossible that we will not find proofs of Emunah.” Rav Chaim Kanievsky shlit”a similarly said it is a davar pashut that we don’t need to be concerned that honest talk about Emunah will be harmful to those who started without questions — it will only benefit. [For more on this, see “Where is the Passion?” by Rabbi Dovid Sapirman, Dialogue, Fall 5775/2014.]

Besides the importance of good parenting generally — and I would recommend again Rabbi Gordimer’s article on parenting — I would add one point about Shabbos guests, especially if they are not observant: they offer a good opportunity to discuss Emunah in front of your children without lecturing them about it.

Our community is by and large doing an excellent job, as the Pew Report shows. While others may be floundering for solutions to problems of diminishing affiliation, we are growing both in numbers and commitment. Yet there is always more that we could be doing, and it is in that spirit that I have offered these suggestions. May every child appreciate the tremendous gift that is his or her Jewish heritage.

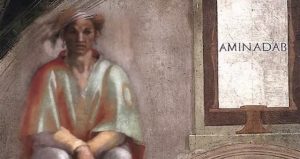

Michelangelo lived at a time when the Catholic Church was increasing its oppression of Jews — he painted the Sistine Chapel in between the Spanish Inquisition and the Portuguese. He was commissioned to paint the chapel with Christian scenes, but petitioned for liberty to do basically as he wished — and the result is almost entirely drawn from the Jewish Bible, emphasizing the connection between the Church and the Jewish nation.

Michelangelo lived at a time when the Catholic Church was increasing its oppression of Jews — he painted the Sistine Chapel in between the Spanish Inquisition and the Portuguese. He was commissioned to paint the chapel with Christian scenes, but petitioned for liberty to do basically as he wished — and the result is almost entirely drawn from the Jewish Bible, emphasizing the connection between the Church and the Jewish nation.

We all know what happened. Matisyahu was invited to the Rototom Sunsplash Reggae Festival. BDS Valencia pulled out the stops to ban the Jew. Rototom demanded that Matisyahu pass an ideological litmus test and endorse yet another Palestinian state. He refused. They banned him.

We all know what happened. Matisyahu was invited to the Rototom Sunsplash Reggae Festival. BDS Valencia pulled out the stops to ban the Jew. Rototom demanded that Matisyahu pass an ideological litmus test and endorse yet another Palestinian state. He refused. They banned him. In this week’s reading, the verse says “Lo Sisgodedu” — “do not cut yourselves,” which was a mourning practice of idolators. But the Medrash tells us that the words give us another messages as well: “do not divide, do not split up.”

In this week’s reading, the verse says “Lo Sisgodedu” — “do not cut yourselves,” which was a mourning practice of idolators. But the Medrash tells us that the words give us another messages as well: “do not divide, do not split up.”